The Ways of the Mountain Men

Part of the Hi-Sierra International Rendezvous

The Stuff of Legends: The Ways of the Mountain Men

The legends and feats of the mountain men have persisted largely because there was a lot of truth to the tales that were told. The life of the mountain man was rough, and one that brought him face to face with death on a regular basis--sometimes through the slow agony of starvation, dehydration, burning heat, or freezing cold and sometimes by the surprise attack of animal or Indian.

The mountain man's life was ruled not by the calendar or the clock but by the climate and seasons. In fall and spring, the men would trap. The start of the season and its length were dictated by the weather. The spring hunt was usually the most profitable, with the pelts still having their winter thickness. Spring season would last until the pelt quality became low. In July, the groups of mountain men and the company suppliers would gather at the summer rendezvous. There, the furs were sold, supplies were bought and company trappers were divided into parties and delegated to various hunting grounds.

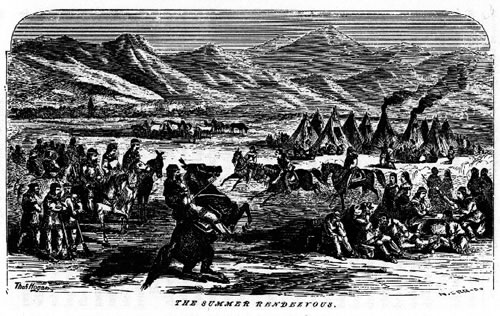

The tradition of the rendezvous was started by General William Ashley's men of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company in 1825. What began as a practical gathering to exchange pelts for supplies and reorganize trapping units evolved into a month long carnival in the middle of the wilderness. The gathering was not confined to trappers, and attracted women and children, Indians, French Canadians, and travelers. Mountain man James Beckworth described the festivities as a scene of "mirth, songs, dancing, shouting, trading, running, jumping, singing, racing, target-shooting, yarns, frolic, with all sorts of extravagances that white men or Indians could invent." An easterner gave his view: "mountain companies are all assembled on this season and make as crazy a set of men I ever saw." There were horse races, running races, target shooting and gambling. Whiskey drinking accompanied all of them.

After rendezvous, the men headed off to their fall trapping grounds. Contrary to the common image of the lonely trapper, the mountain men usually traveled in brigades of 40 to 60, including camp tenders and meat hunters. From the brigade base camps, they would fan out to trap in parties of two or three. It was then that the trappers were most vulnerable to Indian attack. Indians were a constant threat to the trappers, and confrontation was common. The Blackfeet were by far the most feared, but the Arikaras and Comaches were also to be avoided. The Shoshone, Crows and Mandans were usually friendly, however, trust between trapper and native was always tenuous. Once the beaver were trapped, they were skinned immediately, allowed to dry, and then folded in half, fur to the inside. Beaver pelts, unlike buffalo robes, were compact, light and very portable. This was essential, as the pelts had to be hauled to rendezvous for trade. It is estimated that 1,000 trappers roamed the American West in this manner from 1820 to 1830, the heyday of the Rocky Mountain fur trade.

In November the streams froze, and the trapper, like his respected nemesis the grizzly bear, went into hibernation. Trapping continued only if the fall had been remarkably poor, or if they were in need of food. Life in the winter camp could be easy or difficult, depending on the weather and availability of food. The greatest enemy was quite often boredom. As at rendezvous, the motley group would have physical contests, play cards, checkers and dominos, tell stories, sing songs and read. Many trappers exchanged well worn books and still others learned to read during the long wait for spring, when they could go out and trap once again.

The equipment of the mountain man was sparse and well used. Osbourne Russell provides an apt description of the typical mountain man from one who was there.

"A Trappers equipment in such cases is generally one Animal upon which is placed...a riding Saddle and bridle a sack containing six Beaver traps a blanket with an extra pair of Moccasins his powder horn and bullet pouch with a belt to which is attached a butcher Knife a small wooden box containing bait for Beaver a Tobacco sack with a pipe and implements for making fire with sometimes a hatchet fastened to the Pommel of his saddle his personal dress is a flannel or cotton shirt (if he is fortunate to obtain one, if not Antelope skin answers the purpose of over and under shirt) a pair of leather breeches with Blanket or smoked Buffalo skin, leggings, a coat made of Blanket or Buffalo robe a hat or Cap of wool, Buffalo or Otter skin his hose are pieces of Blanket lapped round his feet which are covered with a pair of Moccasins made of Dressed Deer Elk or Buffaloe skins with his long hair falling loosely over his shoulders complete the uniform."

Filling in the Map: Explorers and Guides

Henry Nash Smith's Virgin Land outlines the myth of the mountain man and the larger-than-life image poplar back in the east. While the mountain men have always been an important symbol of America's wild frontier, their role in westward expansion was also very concrete. Most mountain men were both adventurous and practical; they came to the wilderness to turn a profit. This desire to make a living and their amazing ability to survive in the wilderness made them ideal trappers during the fur heyday and kept them in the mountains long after the beaver were gone. They became explorers, guides and even government officials. The mountain men did not just wander around the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains creating material for adventure stories and tall tales, they were instrumental in exploring and settling the land west of the Mississippi.

The first American fur trading expedition was formed by John Jacob Astor. He hoped to cross the continent overland and by sea, and create a trading post at the mouth of the Columbia River. William Price Hunt used the information supplied by the Lewis and Clark expedition to lead the overland Astorians. They reached the mouth of the Columbia in February of 1812 where the fort "Astoria" had already been erected by the seafaring group that had arrived months earlier. Leading the return overland expedition was Robert Stuart. This group would lay the groundwork for the Oregon Trail by finding the South Pass through the Rocky Mountains, a route that had eluded both the Lewis and Clark expedition and Hunt. The discovery of the South Pass was the key to a continental passage by land. The importance of Stuart's feat was recognized immediately, though the Missouri Gazette exaggerated the ease with which a crossing could be done: "By information received of these gentlemen, it appears that a journey across the continent of North America might be performed with a wagon."

To find men for the first expedition of what would become the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, William Ashley and Andrew Henry ran this advertisement in the St. Louis Gazette and Public Advertiser in the winter of 1822: "Enterprising Young Men...to ascend the Missouri to its source, there to be employed for one, two, or three years." Answering the call were such names as Jedediah Smith, Etienne Provost (after whom Provo Utah would be named), Jim Bridger, Thomas Fitzpatrick, and Hugh Glass (about whom the book Lord Grizzly was written). Smith quickly proved himself and became the leader of subsequent parties from 1823-1830. Smith explored both the Rocky Mountains and the southwest. Over the course of his explorations he rediscovered the South Pass, went all the way to Arizona, across the Mojave desert to California and back across the Great Basin. Though Smith was killed before he could edit his papers and perfect his maps, a record of his explorations was brought to attention when Ashley was elected to the House of Representatives in 1831. There, the documents became Senate document 39 of the 2nd session of the 21st congress of the United States. Although the papers did not nearly reflect the vastness of Smith's experience, they offered a fair presentation of the potential of the west.

Smith's case was typical. All of the mountain men had a picture of the land in their mind's eye, but they lacked the skill and means to put it to paper and send it back east. So until the 1840's a correct, comprehensive map had yet to be drawn.

After the decline in the beaver trade and the final rendezvous in 1840, the mountain men needed to find other means to support their lives in the wilderness. During the summer of 1845 alone an estimated 5,000 emigrants went west. These emigrant trains from the east and government surveying expeditions provided a new realm of employment for the trappers. Military service was often the natural progression for trappers who guided for surveying expeditions. Sometimes the trappers joined the service out of loyalty to a particular officer, or because they were in the right place at the right time. Actual titles were not often needed and sometimes only given after long service.

Kit Carson was one of these men. In 1842 he joined Lieutenant John C. Fremont, Corps of Topographical Engineers, U.S. Army, on an expedition to survey the Platte and Sweetwater Rivers as far as the South Pass. The expedition certainly did not chart unknown territory, but Fremont's reports, edited by his wife Jessie, heated public desire for westward expansion. These same reports began Kit Carson's career as an icon of the west.

Carson would accompany Fremont on two more expeditions and as a result of these military connections, fight in the Mexican War. He would continue to serve his country as an Indian agent for the Ute Indians in Taos from 1853-1861. When the Civil War broke out, Carson eventually rose to the rank of Brigadier General.

Jim Bridger also turned to a service career after the collapse of the fur trade. He established Fort Bridger near the Oregon and California Trails and provided well needed supplies for the wave of emigrants from 1842-1848. Bridger's guiding resume is also long and distinguished. He guided Captain Howard Stanbury through what would become Bridger's Pass in 1850. This route shortened the Oregon Trail by 61 miles and would eventually be the route of the overland mail, the Union Pacific Railroad, and even Interstate 80.

Bridger's first military title, though questionable, was that of major bestowed on him by Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston during the Mormon conflict of 1857. In 1859, Bridger led Captain Raynold's surveying expedition to the Yellowstone area. For the next 8 years he would guide and counsel military commanders in the opening campaigns of the war with the Sioux Indians. Thomas Fitzpatrick also wore many hats in the opening of the west. Like Carson, he accompanied Fremont on his second expedition, and in 1842, he led the very first missionary/emigrant group of Bidwell and Bartleson to California. This group was also the first to stop at newly erected Fort Bridger. In 1845, Fitzpatrick led Colonel Stephan Watts Kearney's trip to establish a military presence on the route to Oregon.

On these expeditions the title of "guide" was many faceted. By the 1840's, most of the routes were well traveled and little geographical guiding was required. However, the trapper-guides did show their charges how to survive in the rough climate of the mountains and more importantly, they also helped them handle the often touchy encounters with Indians.

The mountain men had a great deal of first hand experience in dealing with Native Americans, and though they were not always sympathetic, they at least understood the Indian. Their experience proved invaluable as they helped military and emigrant parties try to avoid conflict. Though often of limited literary capacity in their native tongue, most mountain men could speak one or more Indian languages and also communicate with sign language. A few of the mountain men even used their skills in a more formal setting: as Indian agents for the federal government.

Though he was an Indian fighter for several years, Kit Carson also served as an agent for the Ute Indians in Taos where he had a reputation for being firm but fair. Thomas Fitzpatrick used his diplomatic skills to smooth over conflicts during his tenure as a guide, and he eventually worked for the Upper Platte and Arkansas Indian agency. There, he inspired the first treaties with the plains Indians at Fort Laramie in 1851 and Fort Atkinson in 1853.

Jim Bridger's long life in the mountains provided him with both the expertise and the opportunity to facilitate relations with the native population. During the expedition through Bridger's Pass in 1850, he saved the surveying excursion of Howard Stansbury from a confrontation with the Ogalalas through his outstanding use of sign language. Bridger also interpreted at the Fort Laramie treaty council in 1851. He continued to advise military commanders through the opening campaigns of the wars with the Sioux.